A closer look at the rapidly changing demographic: How and when we got the vote may help us to keep it.

Racial minority groups in the United States have long burdened the load as this nation’s moral compass, while at the same time serving as a driving force for change. Over the last 150 years, these communities have provided innumerable examples of how to show up in times of turbulence and how to act on the right side of history. In times such as these, it can be helpful to reflect on the histories of resilience and activism that have defined these communities to position the present in sharper, if not more familiar, focus - and to challenge us to consider our own priorities as we look for ways to learn and act this November.

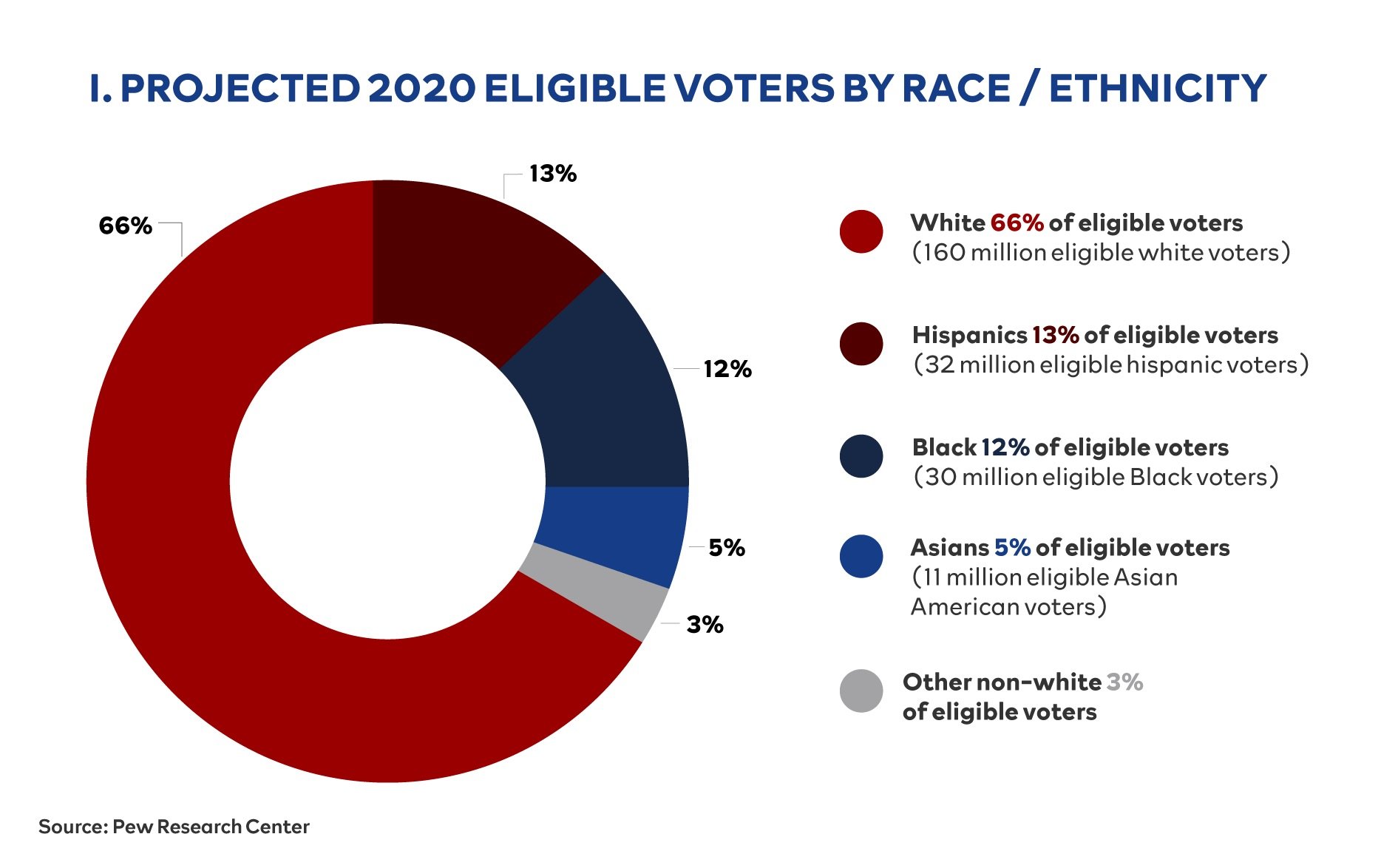

Today, the rapidly changing demographic makeup of the U.S. has made it one of the most racially and ethnically diverse nations on the planet. Yet, Americans continue to wrestle with fundamental questions of race and the electorate. A century and a half after Frederick Douglass first warned of the importance of the vote, daily news sounds the siren of a nation at an inflection point. With a critical presidential election just days away, voter intimidation is on the rise, entire families are in the streets raising their voices in the largest sustained movement for racial justice in U.S. history and swirling poll reports warn of election manipulation and efforts to discourage Black and Brown communities from voting. The truth is that we have always been a nation teetering on this exact edge: aspiring toward a more possible, equitable future, and at the same time, frightened and clinging to the rigidity of the past.

On a cold spring morning in New York in 1865, Frederick Douglass issued a sober reminder before a bustling crowd of fellow abolitionists when he proclaimed that “slavery is not abolished until the Black man has the ballot.” With the formal signing of the emancipation proclamation weeks before, Douglass articulated this clear-headed call both as a comment on what the government was conceding but perhaps more importantly, as a comment on the focused fight that lay ahead. True to the litany of insightful forecasts about race, literacy, abolition and equity that are attributed to Douglass’ life, the fight to “have the ballot” would become one of the most critical, contentious and moral issues in American democratic life.

Black Suffrage

From the moment the Civil War ended in America and newly freed slaves were guaranteed citizenship through constitutional amendments, Black Americans faced violence and backlash. From the immediate formation of the Ku Klux Klan to the strategic granting of citizenship without voting rights, the initial Reconstruction Era was categorized by aspirational federal legislation alongside limited intervention in state-sanctioned terrorism and policies targeted toward Black communities. While Black men (not women) were granted the right to vote in 1867, for example, the immediate years following marked the highest recorded numbers of terror lynchings in American history. This period also gave states the power to adopt Jim Crow Laws that legalized the enforcement of public segregation, and allowed the use of “grandfather clauses,” poll taxes, and literacy tests to keep Black voters away from the voting booths.

While this smoke-and-mirrors cycle of unfulfilled promises fortified a distrust between Black voters and the new democracy, grassroots organizers mobilized around the vote in different ways following the Second World War. Building on the legacy and labor of the strongest consolidation of civil rights action the United States has ever witnessed, organizers protested, sat in, stood up, lobbied, marched, strategized, fought, and gave their lives to see the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

First Americans

For Indigenous communities, the path to franchise has been, in many ways, even more fraught with complexity and contradiction. Although the 15th Amendment passed in 1870, and the 19th Amendment passed in 1920, it wasn’t until 1924 that American Indigenous communities were granted non-voting citizenship - and 1962 that they gained voting rights in all states. Ironically perhaps, indigenous communities practiced effective self-government in America for centuries before the formation of the United States government. Much like the experience of Black voters, American Indians have continually combatted subversive state efforts to suppress and restrict religious and legal rights, land use, language access, and family protection services.

Among the many activist stories often highlighted in the fight that indigenous peoples faced to gain access to the vote is that of Miguel Trujillo, a WWII veteran who upon returning home after his military service filed a lawsuit with the state of New Mexico that would ultimately snowball into the passage of the universal Voting Rights Act of 1965.

El Voto Latino

Like Black Americans and indigenous communities, Latinx communities officially gained the right to vote in 1965 through the Voting Rights Act, yet it was a full decade later that this right was extended to the millions of Spanish-speaking Latinx citizens who remained unprotected “language minorities” under the initial legislation. Prior to that, Latinx peoples’ relationship to the voting process was not dissimilar from the experience of indigenous communities: Anglo settlers declared war in pursuit of manifest destiny, which resulted in the simultaneous granting of citizenship and institution of laws to disenfranchise Mexicans in Texas. As early as the 1910s however, Chicano labor organizers began building coalitions to advocate for workers rights and access to education. In concert with other civil rights movements across the country, Latinx activist communities won small victories in the form of work programs, segregation lawsuits, successful school walk-outs, and bilingual support programs. Those achievements were met with violent backlash and strategic federal efforts to appease through legislation while endorsing state-level disenfranchisement.

Asians Rising

Asian Americans have their own rich history of exclusion from the voting process. Beginning with the other Naturalization Act of 1790, which limited citizenship to “free white persons of good character,” and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1890, the first law to ever ban a specific ethnic group from naturalizing, the xenophobic history of Asian exclusionism is both familiar and disheartening. In much the same way that loopholes between federal and state legislation allowed and encouraged violence and discrimination against Black, Indigenous and Latinx voters, so too was that true for Asian American communities.

Ultimately, it was again the Voting Rights Act that would enable Asian Americans the opportunity to vote, and more importantly, enable the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act which abolished the quota system for immigration practices and allow immigrant families to reunite - many of which fled from countries warn-torn by U.S. conflicts. In fact, however, it was only through the work of countless Asian American coalitions and movement builders like Fred Korematsu, Grace Lee Boggs, Kiyoshi Kuromiya, and Larry Itliong, that the franchise for Asian Americans was ultimately secured.

Continued Challenges to Universal Suffrage

The simplification of this history is not intended to represent the struggle for enfranchisement, rather it is intended to situate these histories, consistently and disproportionately sidelined within our larger democratic process, in the very real moment of today. The 2013 Supreme Court ruling in Shelby v. Holder effectively upended many voting rights gained through the original legislation, and there are many reports that state voter suppression is mounting as a result. These histories, then, are intended to offer insight into why the “fight for the ballot” continues to be of such consequence in this moment - which is both unique and familiar.

Currently, 36 states require that voters show photo ID to vote, adding an additional cost and administrative burden to the process. Some states are reducing early voting, while others have been found closing polling sites early on election day, which presents difficulties for working, low income families. States are failing to offer translation and language services. There have been reports of purged voter lists, and redrawn voting lines to confuse and complicate voters in certain communities. And some states and localities have been granted permission to consolidate polling places, which many argue has been done strategically to impede the vote for communities of color in the South. If this sounds familiar, it should.

More than a century after Fredrick Douglass addressed those crowds in New York, the same tactics are being called upon to keep Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities from showing up and being counted. The same fear and pessimism is being conjured up to convince us there are good people on both sides. We have been here before - but these histories of resilience remind us that it isn't who we are. They remind us that while the arc of the moral universe may bend toward justice, it does so because we, the people, make the choice to act and disrupt and vote in incisive moments such as these were history would otherwise simply happen to us.

The largest and most sustained protest for racial justice in this nation’s history rages daily in the streets of our cities, on our bridges, in our parks, where despite our fear of an unprecedented global pandemic, we strap on our masks and join thousands to say his name: George Floyd. To say her name: Breonna Taylor. To say the names of countless men and women whose lives and families matter. To admit to ourselves that we know we are teetering on the edge of a moment, and that perhaps it is our only great task to not sit still.

Supplemental Resources for Awareness & Action

A handful of organizations working to activate awareness around Indigenous issues and voter access include:

Many young Latinx activists are leading the charge on climate activism and calling for solidarity with the Movement for Black Lives. Established organizations working to create awareness around these issues and voter access for Latinx people include:

-

• Voto Latino,

-

• Poder Latinx,

-

• and United We Dream.

Young Latinx activist to follow on these issues include Miss Sara Mora, Prisca Dorcas Mojica Rodriguez, Elizabeth Acevedo, and some of the countless shoulders they’re standing on.

Current organizations and activists working to amplify awareness around the Black vote include:

For a national list of Black-led organizations working in priority states, and offering locally-specific instructions for Black voters in 2020, visit and support the Black-Led Organizing Fund.

Asian Americans are working to exercise their voting rights through organizations like:

-

• APIA Vote,

The National Network for Immigrant and Refugee Rights offers a range of resources to support immigrants’ civic participation and voting rights.

Dr. Adam Falkner is a poet, educator and arts & culture strategist whose work has appeared in a range of print and media spaces. Falkner is the Founder and Executive Director of the pioneering diversity consulting initiative, the Dialogue Arts Project, and was the featured performer at President Obama’s Grassroots Ball at the 2009 Presidential Inauguration. He holds a Ph.D. in English and Education from Columbia University.